It seems like the quickest way to make a billion dollars at the moment is to create a successful internet platform. Companies like Facebook, eBay, Airbnb, Twitter and Paypal are platforms that have gone from obscurity to internet giants in a matter of years. So what are these platforms and how are they making so much money? A lot of starry-eyed tech entrepreneurs wax lyrical with theories that equate the technology revolution to a revolution in business and economics. But the typical way an internet platform makes profit is by acting as a two sided market, which is a type of business that existed long before the internet.

Two sided markets are naturally able to thrive at huge scales and platforms have been taking advantage of this, attaining unbelievable valuations. It is useful to view internet platforms through the lens of a two sided market because it explains the incentive structure of the platform and how the companies orient themselves in terms of product decisions.

This blog post first describes network effects, an economic concept that helps you understand two sided markets. It then goes on to describe the structure of a two sided market and who to incentivise within it. The post ends by showing how many internet companies have structured themselves around a two sided market principle. There is no maths in this post and the concepts discussed require no background knowledge.

Network effects

There are some products and services that become more valuable if more people are using them. For example think of e-mail. If there were only two people in the world who had e-mail, they would only be able to talk to each other and the service would not be very valuable. When a third person gets e-mail, the service becomes more valuable to the original two users as now they can contact someone else. When a fourth person gets e-mail, the other users find it more valuable as they can contact more people on it. Every time a new person gets e-mail, everyone already using e-mail benefits a bit more because they can talk to more people.

This phenomenon is called a network effect and it occurs in a large amount of internet services. When everyone uses the same product and they are all benefiting from doing so, it’s good news for whoever makes the product. Take Facebook as another example. I know a lot of people who want to delete their Facebook account but don’t because it is so easy to contact everyone they know on it. This is a network effect. So many people have Facebook that it is effectively a directory of people, making it a valuable service. Every time a new member joins Facebook everyone benefits a bit more. This value only exists because of the amount of people that use it and doesn’t have much to do with Facebook itself (you could try and contact people on Myspace, a service very similar to Facebook, but no-one uses it so it isn’t very valuable).

When there are multiple companies offering a product that has network effects, you can quite easily show that everyone benefits the most if they all use the same product. For instance if there were hundreds of social networks with only a few thousand people on each one, the users wouldn’t benefit as much as they would if they all used Facebook. This is because of the network effect.

This ‘all or nothing’ aspect of network effects can lead to some interesting market dynamics. When two products that rely on network effects are competing against each other, there will usually be a ‘tipping point’ where everyone suddenly starts banding together to buy one product, leaving the other product useless. A great example of this is the Bluray vs HD DVD saga.

Bluray and HD DVD are products that provide better quality video than DVDs and both rely on network effects. Bluray becomes more valuable if more people have Bluray, as you can then share movies and you can be sure that the newest releases will be in your format. The same goes for HD DVD. If everyone bands together around a common video format everyone benefits.

The graph below shows the pivotal week in the competition of Bluray vs HD DVD. In a week Bluray went from having a 51% market share to a 92% market share. This was the week that Warner Brothers announced it would support Bluray devices only, and not HD DVD. You can see that this was the ‘tipping point’: everyone decided to use Bluray and leave HD DVD to wither away.

So we’ve seen how network effects are a quality of many internet products and that they can be vital in determining the success of a business. However network effects don’t only occur in certain types of product, there are also businesses that use network effects in their structure. Namely two sided markets.

Two Sided Markets

A two sided market is a business that brings two groups of people together. The structure is shown below:

The most basic example of a two sided market is, quite literally, a marketplace. One group would be farmers or food sellers, the other group would be people who want to buy food. The marketplace is where the two groups meet. The business’ value is providing a space in which these two groups can interact and it makes money by charging farmers to have a stall in that space.

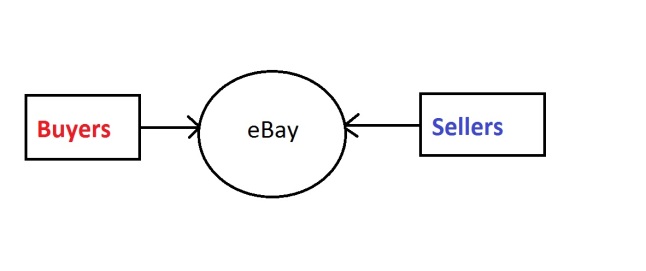

This structure is how most internet platforms make their money. They bring two groups of people together and charge one (or both) groups to do so. Lets take an example of an internet marketplace: eBay

Just like a marketplace in real life, eBay provides a space where people who want to sell something and people who want to buy something can interact (through an auction). The way that eBay makes money is by charging the sellers whenever they list something, just like how farmers pay for a stall.

The network effects in two sided markets are slightly different to what I described above. In the examples above there is one group, the consumers of the product, who benefit when more people join their group i.e. when more people use the product. E-mail users benefit when more people use e-mail, Facebook users benefit when more people use Facebook. Like the diagram below:

What is different in two sided markets is that Group A benefits when there are more people in Group B and vice versa. Members of Group A don’t really care how many people are in their group, they care about the other one. This is shown below:

The way to get your head around this is by imagining that sellers on eBay only sold one product, say sofas. If there was 1 person selling a sofa and 10 people looking to buy a sofa, the seller will be happy because the buyers will probably aggressively bid and the seller will get a good price for it. Furthermore, if an extra person wants to buy a sofa, the seller is happier because he will contribute in bidding to a high price. Conversely if there was 1 person wanting to buy a sofa and 10 people selling, the buyer will be happy because the he can look for the cheapest sofa rather than having to compete with other buyers. If an extra person wants to sell a sofa the buyer is more happy because he might provide a better deal. The buyers benefit if there are more sellers, the sellers benefit if there are more buyers. This is the network effect in a two sided market [NOTE: each group does benefit if there are more people in it, but in an indirect way that I won’t describe].

We’ve seen how in a two sided market each group cares about how many people are in the other group. So how does a company like eBay use this information to their advantage? They use it to structure the incentives for each group, as the two relationships are usually not equal. This unequal balance of relationships is best highlighted by the classic way an internet platform makes money, the quarter pounder with cheese: connecting advertisers and consumers.

The Advertising Model

The way that Google, Facebook, Twitter, News websites, Hulu and more make the main bulk of their money is by connecting advertisers to consumers:

All these services are two sided markets because they provide a space where consumers and advertisers can interact. However the relationship here is clearly skewed towards advertisers. If there are lots of consumers looking at the adverts then the advertisers are happy. When more consumers are in the market the advertisers get much happier, they therefore strongly benefit from the relationship. The consumers don’t get as good a deal. If there are more adverts available to be shown to you, there is an argument that the consumer would benefit from more targeted advertising, however it’s not that beneficial: on the whole people don’t like adverts.

Because the advertisers benefit from the relationship so much more than the consumers, it makes sense for the platform to incentivise the consumers with its products. Advertisers gain value from the relationship, whereas consumers don’t. Therefore consumers need get value from somewhere. This is where services like Google search, Facebook’s social network and Twitter’s feed come in. These are useful products that are there to incentivise the consumer to come to the market and interact with advertisers. In fact consumers often have to pay no cost to use the service, as they need to be incentivised a lot. Advertisers are where these platforms get their money, because they find the relationship so useful that they are willing to pay good money for it.

This can be summed up in a rule that is general for any two sided market:

In a two sided market, incentivise the group that benefits least from the relationship

Buyer/Seller Model

We’ve already seen how eBay works as a two sided market:

This is the same model as a number of other different services, where a space is provided from people to buy and sell items. For instance Amazon selling third party books, the Google Play store/Apple App store, Zoopla and car insurance websites use this model. In almost all of these cases the person selling the product is charged to be in the market, whereas the buyer doesn’t pay anything (directly). This is because it is assumed that the person selling the product benefits a lot when there are a lot of buyers, whereas buyers don’t benefit as much when there are a lot of sellers. Therefore the people selling good pay the cost.

Note in the relationship in this model is more equal than the advertising model. Buyers may not benefit as much as sellers in the relationship, however when there are more people selling a good that is still a big benefit for the buyers. Because of the more equal relationship, the incentives don’t have to be as big. I know that there are lots of people selling the same copy of a book on Amazon, so it will probably be cheap, and that’s a good enough reason for me to go to the market. In advertising I need a cool free product to be incentivised, in a buyer/seller market I don’t need a free product, I just need to know that I will be able to buy something at a good price.

Airbnb

Airbnb is an internet platform where people rent out their homes to visitors who stay for a few days. It is like the buyer/seller model in that someone is selling time in a house to someone who wants to buy it, however the relationship in this scenario is slightly different.

Airbnb charge both guest and host fees, i.e. they charge both groups for doing business in the market. This isn’t uncommon, though it is less likely in internet platforms. What is interesting is that the guest has to pay higher fees, i.e. the buyer pays the main cost rather than the seller. This implies that Airbnb think that guests have a lot to gain when there are many hosts, whereas hosts don’t gain as much with many different guests, and this makes sense. When going on Airbnb it is great when there are lots of different places to choose from in a city, each place has a different character and the customer gains value each time a new place is added. The hosts however don’t have as much of a benefit. If there are lots of different guests you might meet some nice people, but most you can gain from a guest is that they leave the place clean. Most guests are pretty much the same so the hosts don’t get much value when there are a lot of them. Therefore because the buyers get more from the relationship, they have to a higher fee in order to incentivise the sellers more.

This blog post has explained network effects and two sided markets, showing how many internet platforms are based on this model. I hope you enjoyed reading it!

Keep writing George: you have a way of explaining things clearly and generally concisely that I certainly appreciate very much. Don’t shy away from maths and more techy posts though, the engineery/tech types (I’m a half breed) that stop by here love it.

good

Nice

Nice

Nice & very good

Good article!